Dressing Up vs. Dressing Down

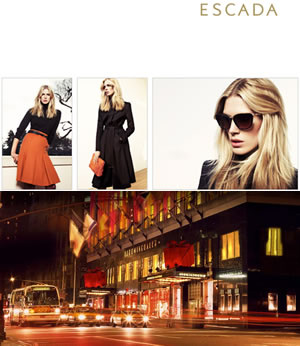

Image credits: Escada and Bloomingdale's

"Hi, would you like me to unchain the coat from the wall so you can try it on?" the Bloomingdale's saleswoman asked me.

"I'm just looking, thanks. This Escada coat is amazing, but forty thousand dollars is quite a lot," I said, standing there in my jogging suit and hooded parka with a backpack full of cheap food for the day (New York fast food was expensive for me, too).

"Dressing down" is generally viewed as a greater virtue than "dressing up" these days. This difference between our generation and our grandmothers' was refreshed to my attention recently when re-reading the classic book by Carole Jackson published in 1980, Color Me Beautiful. After laying out her rules for which clothing colors enhance various skin tones, Jackson gave shopping advice, "Dressing well when you shop gives you two advantages: you will be better able to judge clothes on yourself, and you will receive better service. It isn't fair, but it is true that salespeople will respond to you according to the way you look" (pages 202-203).

Fashion analysts since Jackson have dispensed with her color rules, saying that the intensity of a color matters more than the shade. Some have suggested that a woman's only color rule should be that if she likes the color, she should wear it (though this still pays tribute to Jackson who said that the colors that look best on us will be the ones we naturally like). As for Jackson's "dress up to receive better service" advice, it may be true in some instances, but I had to smile when reading as I thought of a story that took place three decades after Jackson wrote those words, in a culture where the effect of dressing up is no longer predictable.

It was a cold, overcast November day in New York City in 2008. My work as an apparel patternmaker since arriving in the city eighteen months earlier had been so intense that I had not had time to visit tourist attractions or designer flagship stores in the "Fashion Capitol of the World," as New York is often called (I have wondered how Parisians view this usurping of what has historically been their title). My plans were to take the Long Island Railroad and connect by subway to the south end of 5th Avenue around Broadway and walk north, taking in as many fashion designer stores as possible, then move east to stores on Madison and Park Avenue if time allowed. Of course I would have loved to equal the impression of well-groomed women shopping in the same area, but they wore high heels for their short walks from luxury hotels or limo service. It would take me two miles of walking to travel round trip to my first train stop and several miles more to navigate the shopping district. So for this occasion, I donned a jogging suit, running shoes, a worn-out hooded rain parka and a backpack full of food. I may not have looked the part of a rich shopper, but I was warm and expected to save a handful of cash by avoiding Manhattan restaurants, the least of which are still expensive.

In this ragged state, I made memorable visits to some of the most renowned designer clothing stores in the world. Salespeople were courteous, if not attentive. Two or three shoppers at once in a high-end store made a crowd. More often, I was the only shopper within view. A co-worker to whom I related my tale said, "All they need to do is sell one thing a day, that's all." The high prices of designer fashion translate to low sales volume, which is why what appears to be an overpriced evening gown may actually not even turn a profit for the company. I had worked for an evening gown designer who sold beaded dresses for as high as ten thousand dollars, and I knew my division operated at a loss, saved only by profit from a mass-produced collection marketed through QVC. So, when I ran across a intricate Escada coat made from multiple types of real fur with leather pieces embossed to look like leaves hand-sewn all over, I understood the forty thousand dollar price tag (actually, I recall it was around forty-two thousand and some odd number).

The Escada store showcased the coat in its front window, but I first saw the coat up close at Bloomingdale's and was admiring the handwork when a saleswoman approached. "Would you like me to unchain the coat from the wall so you can try it on?" she asked.

Had I been dressed even a little bit better, such as in a denim skirt and blouse such as I normally wore to work, I would not have been as surprised by her offer. However, in my outfit that day, worn for warmth in the face of miles of walking, I looked like a hiker from a mountain trail. When she approached, I had been thinking how that some houses in the Midwestern United States could be purchased for forty thousand dollars. "I'm just looking, thanks. . . . Forty thousand dollars is quite a lot," I replied, as if she couldn't tell by looking at me that I wasn't in the market for the purchase.

"Okay, well let me know if you change your mind," she said, and walked off. She had just treated me as though I were a millionaire in hiding. Who knows? Maybe other millionaires dress down when they shop, just like I had that day. Ever since, I have thought of that saleswoman's cheerful courtesy as proof that in the 21st Century, dressing up not always a prerequisite to receiving better service.